I bethought me that a bird capable of addressing a man must have the right of a man to a civil answer; perhaps, as a bird, even a greater claim.

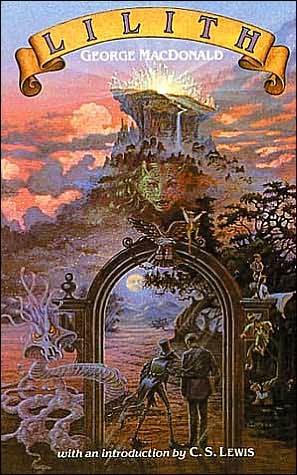

In his 80s, MacDonald was finally ready to compose his masterpiece, the dense and genuinely weird—in all senses of that word—Lilith. Like his earlier fantasy novel, Phantastes, Lilith tells the story of a young man who leaves his house to travel in a strange, mystical world. But where Phantastes worked with the language of fairy tales, Lilith draws from tales of hell, vampires, Jewish mythology and Christian thought to create a richer, deeper work, overlaid with outright horror. It is a book written by a man at the end of his life, contemplating death, using the language and symbols of allegory without clarifying what it might be allegorizing. It has moments of strange beauty: worms shifting into butterflies, people feeding grapes to corpses, skeletons doing Shakespearean dances.

Oh, and constant exclamation points! Like this! And this! And this! Sometimes even justified!

And, alas, the return of terrible poetry. I suppose a masterpiece can’t have everything.

As the book begins, young Mr. Vane (the pun is deliberate) finds himself haunted by the ghost of the family librarian, a proper sort who likes to steal books. (I thoroughly approve.) The ghost also has the tendency to shift into the form of a raven. This is, in part, a reference to the old Scottish and Norse tales of ravens, birds of ill omen and wisdom (and in some tales, the ghosts of murderers), and to Odin’s ravens that see and hear all. But the raven also appears in Biblical stories, particularly in the story of Noah’s ark (where Noah sends a raven to find dry land). Clearly this is not an ordinary ghost, a point proven when Mr. Raven helps to pull Mr. Vane into an odd land indeed.

Mr. Raven calls it the land of seven dimensions, never quite explaining what he means by that, but then again, as befits a raven sort of ghost, he never quite explains what he means by anything, even though he’s quite fond of random gnomic sayings. (One highlight of the first part of the book: his observations of just how clueless Mr. Vane is.) But as Mr. Vane continues to travel, he realizes that he is in a land of demons and the dead, a peculiar place of innocent children and mysterious leopardesses and Lilith, the first wife of Adam of Adam and Eve fame, and here, a vampire with long hair and certain dealings with mirrors (both pulled from tradition.)

Vane frequently lives up to his name, and can be short tempered and annoying. He is the sort of guy who pursues a woman even when she expressly informs him that she’s not interested, and then, the instant she changes her mind and is interested, decides that she fills him with loathing. Okay, yes, she’s the embodiment of evil, but I’m just saying: consistency, not this guy’s strong point. Inability to follow excellent advice, that, he’s good at.

But to be fair, the book is filled with these sorts of abrupt changes, adding to the unreal and dreamlike feeling of the entire tale. (Helped by the inexplicable appearance of elephants.) This is especially true when the book reveals Mr. Raven’s true identity, which if not exactly a surprise by this point in the story, leads to one chief nagging question: how exactly did the guy become the family librarian in the first place, or was this just a nice story he told the family retainers to lull their suspicions? Other oddities: a leopardess who wears crocodile leather shoes and drinks the blood of children, rich people admitting that as soon as someone turns poor, the poor person is forgotten since the goal is to stay rich and you can’t do that if you have a single thought about poor people (not MacDonald’s only bitter social comment here).

The book does have one other…odd…scene, where the narrator, a very clearly adult male, if one with some growing up to do, finds children climbing into his bed each night, and, er, hugging him. He explains, probably unnecessarily, that he loves them more than he can tell, even though they don’t know much, and adds, probably a little too happily, that he “unconsciously” clasped them to his bosom when “one crawled in there.” I could attempt to dismiss these children as dreams—they seem to be just dropping from trees in a land where nothing is precisely real—except, well, they aren’t, and Vane actually falls in love with one of them, named Lona, knowing full well she is a child.

Later, this guy eagerly decides to spend a night under a full moon clasping what appears to be the naked corpse of a beautiful woman—to be fair, after he’s tried to feed the corpse some grapes—but you should be getting the idea that this book has some seriously disturbing bits. (I’m pleased to note that after a few months—yes, months—have passed the corpse turns out to be not too thrilled with any of this, either, and hits him, hard. I felt better.) And, still later, he apparently sleeps with a crocodile shoe wearing leopardess, although, you know, even though she licks him all over, and he’s amazingly energized and happy afterwards it’s all PERFECTLY INNOCENT.

Maybe.

Also have I mentioned that Lona and the corpse are fairly closely related, like, mother/daughter related? And that the Victorians liked to conceal their porn in unexpected places? I should probably move on now.

Except that the sex never gets any less strange—the corpse scene is followed by a scene straight from a vampire novel, as the narrator sleeps, then feels distinct pleasure, then pain piercing his heart again and again; when he awakes, he finds Lilith standing there filled with, ahem, “satisfied passion,” who then wipes away a streak of red from her mouth. Vane primly describes this as, ahem, feeding, but with all the pleasure, clearly a bit more is going on here, even if Vane can’t remember the details. And Vane later kinda apparently falls in love with a horse, but I’m just going to move right past that. Really, this time.

Except to note once again: this is one very weird book.

I’m also going to leap right over the question of whether Lilith is a work of Calvinist or Universalist theology, largely because I don’t think it matters: this is less a work of theology and more an exploration of the journey of one human soul. But I do want to address another criticism: the critique that MacDonald has seriously misunderstood Christian theology in the book’s declaration that God is capable of forgiving anyone, even joyful blood sucking vampires (quick: alert the sparkling Cullens). MacDonald certainly makes this point. But, and I think this is important, this universal forgiveness occurs in a land of horror and pain. I may be misreading the text (I get the sense that this is an easy book to misinterpret), but the larger point here seems to be not universal forgiveness, but that forgiveness can be found even in the depths of horror and fear and death. And that forgiveness is not an easy path.

I have another concern: for all of his travels and visitations with death and marching childish armies on elephants against demons (seriously, weird book!) I get no sense, at the end, that Mr. Vane has learned anything at all. I do get the sense that he has transformed from a reader of Dante to a person hallucinating that his books are about to leap from their bookcases and kill him. But the hallucinations and mental illness suggested by the end of the book (and by parts of the middle; the inexplicable and confusing bits may be caused by the narrator’s mental illness, although MacDonald deliberately leaves this point vague) are not character growth, although they are changes. And while I can certainly understand that journeying through the land of seven dimensions and dealing with the evil of Lilith could cause mental illness, I somehow need something more as a result.

I hardly know whether or not to recommend this book. Even leaving aside the weird sexual bits, this is not an easy read: the language is both dense and compact all at once, and highly symbolic, and I think it needs to be read at least twice, if not more, to be understood, if it can be understood even then. And those with a dislike of constant! exclamation marks! should be on their guard; the use here is ubiquitous to the point of annoying even readers who like exclamation marks. It has a grand total of one cheery moment, when MacDonald assures us that God can save us all, even the rich (certain Gospel indications to the contrary) and even corpse like demons who have dedicated their lives to evil and killed their daughters. Certainly not a book to read while depressed. And it actually contains the sentence, which I am quoting directly: “Are the rivers the glad of the princess?” asked Luva. “They are not her juice, for they are not red!”

But MacDonald has never been so imaginative, nor so fantastic, and readers of weird fiction may well want to seek this out. It’s a maddening read, but an unquestionably unforgettable one, and many of its images will haunt readers for a long time.

Mari Ness couldn’t help wondering if the corpse would have responded more kindly, or at least faster, to chocolate instead of grapes. She lives in central Florida and honestly doesn’t spend as much time thinking about feeding corpses as that earlier sentence might imply.